by Nancy Martin

Alameda Museum recently accepted a dress for the collection from the 1890s that features massive leg-o-mutton sleeves. The dress belonged to Kate Moynihan, an Irish émigré to San Francisco who moved to Alameda with her husband, Fred Brampton, after 1880. They resided at 2024 Pacific Avenue, where Fred worked first as a policeman, then as a butcher. They had four children: Louise, Edith, Albert, and Florence.

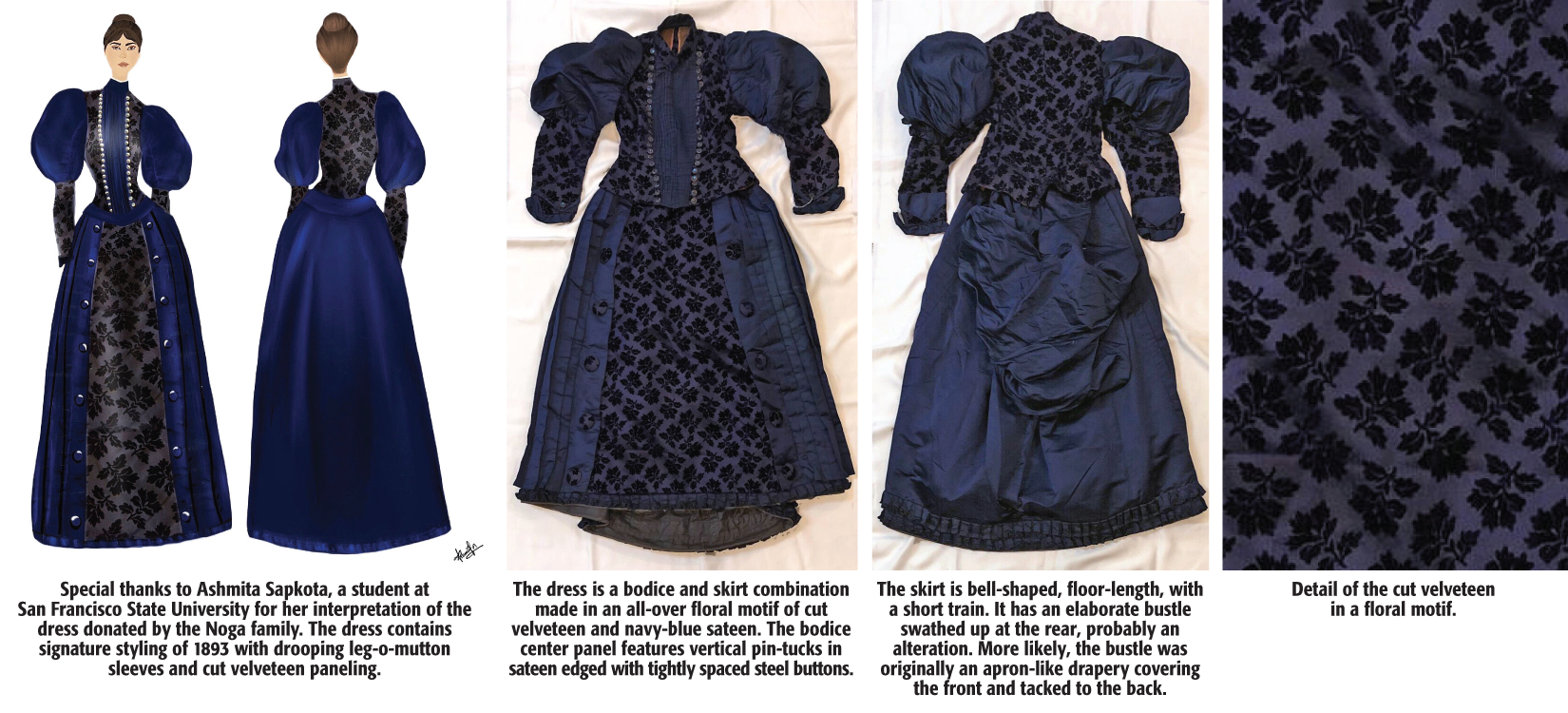

Florence, who inherited the dress, was born in 1891, attended Height School and Alameda High School, then graduated from Healds Business School. She married William R. Francis, who worked in city engineering. They also lived in Alameda homes at 1725 Paru, then at 1989 Stanton, and had three children: Warren, Robert, and Dorothy. Florence lived for over 101 years, and the dress eventually was passed to her grandson Glenn, who currently resides in Lafayette. The dress acquisition is significant to the museum as it is one of the older garments in the collection.

The museum has several less fancy dresses from this same era. According to author Joan Severa, sleeve styles spanned this wide during the 1890s. They are a reliable system of garment dating because, in just five years, they expanded from little puffs at the shoulder to broad horizontal extensions. She notes in Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion 1840-1900 that by 1893, sleeves show the distinctive “drooping” feature observable in this dress. What factors influence sleeves to take such a dramatic form during this era?

Sleeves grew to similar widths during the 1980s in line with the pervasive adoption of shoulder pads. During that era, power suits with extended shoulders signaled a shift in American culture and communicated female aspirations toward equal status to men in the workplace. Not limited to professional attire, shoulder pads were included with every top available in the marketplace and diffused into other forms. Laura Ashley, for example, reintroduced wide ruffles beginning at the shoulder leg-o-mutton sleeves reminiscent of the Gibson Girl. Sleeve widths “seemed to [symbolize] woman’s

increasing place in the world,” reinforcing messages from other social outlets, such as the film 9 to 5 featuring women’s workplace empowerment or Sandra Day O’Connor’s nomination to the Supreme Court. Perhaps this dress reflects similar directions.

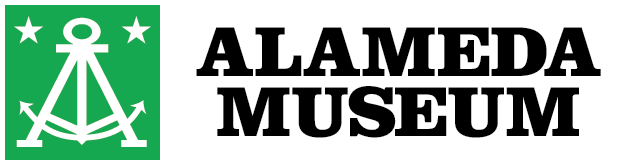

The dress is a bodice and skirt combination made in an all-over floral motif of cut velveteen and navy-blue sateen. The fabric is fashionable for the time and though up-market, shows moderation in its cotton makeup. The bodice center panel features vertical pin-tucks in sateen edged with tightly spaced steel buttons. The side panels are made with patterned velveteen and feature a tiny patch pocket. The sleeve is made in two parts; the cut velveteen undersleeve finishes at the wrist with a pointed cuff and small ruffle, whereas the leg-o-mutton oversleeve in navy sateen ends at the elbow. The bodice, at the center front, is slightly pointy and extends to the high hip level. The skirt is bell-shaped, floor-length, with a short train. Following the bodice style, the center panel is made of cut velveteen framed by wide pleats tacked down with large, covered buttons. The details include a small ruffle at the hem and an invisible pocket inserted into the left side seam. Currently, the dress has an elaborate sateen bustle swathed up asymmetrically at the rear, determined to be an alteration. More likely, the bustle was originally an apron-like drapery covering the front and tacked to the back. Fullness remains at the rear, where tightly spaced cartridge pleats have been folded under to add lift. It may have been supported with a small bustle, like the BVD spiral bustle, “the only bustle that will not break down.”

The garment’s focus, the sleeves are characterized by volume that expands the individual’s boundary in space. The silhouette presents a solid and structured form, yet the sleeves and bustle are moving parts that would express themselves in a rustle as the wearer walks. Not only do they move, but they droop. The aesthetic dress movement of the 1880s may have initiated this character which gave the wearer “a languid, drooping appearance that contrasted with the stiffly constructed lines of fashionable, bustle-supported dresses.” This drooping feature would also move with the figure. However, the sateen fabric has a starchy hand that maintains its volume.

The series of photographs included with the donation supports evidence found in the dress. The individual in this photograph would be very fashion-forward with her high topknot and generous sleeves. How the photos and garment are connected has not been established, though they date to the same time—1890—by the figures’ distinctive hairstyle and sleeves. This series of photos represents innovation in photography that affected everyday people. The introduction of roll film by Eastman Kodak enabled photographs to be taken quickly and in succession. With the invention in 1893, the company marketed the snapshot camera and an advertising campaign featuring “The Kodak Girl,” encouraging women to take on amateur and candid photography. They “targeted women as photographers and subjects, encouraging them in the decades that followed to regard snapshot photography as both a fashionable activity and a domestic duty.” During the 1890s, the use of both cameras and bicycles emphasized women’s growing independence, activity, and mobility outside the home.

In its final reading, the dress exhibits a mixture of styles representative of female dress during the late 1800s. The textures, volume, and layering in deep and saturated jewel tones imply prosperity, a characteristic repeated in the number of glittery metal buttons and ornate tucking. Though sumptuous, the fabrics were made of cotton, a fiber available to everyone. This era was optimistic and known for increasing democratization, economic prosperity, and political tranquility. The social climate was in flux, offering opportunities for women to work or participate in sports such as bicycle riding. For the first time, it became acceptable for women to be outside on their own.

Fashions reflect the “spirit of the times.” Kate Moynihan would have been approximately 37 years old when this dress was made. Though quite fashionable, it exhibits the tendency for mature women to hold on to styles longer than entirely up to date. Wearing this dress, Kate expresses her willingness to embrace the new stylish mode while clinging to past fashions. The bustle, for example, represents a holdover from the previous decade.

The heavy crinoline interlining was dropped by 1893 to accommodate bicycle riding. Skirt lengths were beginning to rise, yet the hem of this dress shows wear to indicate that it did not clear the floor. The heavy dome shape, floor-length skirt, and double rows of metal buttons reference the previous decade, whereas the leg ’o mutton sleeves, the pockets, and cut velveteen are up-to-the-minute fashionable. Most notably, the tiny nonfunctional patch pocket and functional inseam pocket mark modernity. Skirts flatten, hems raise and stays shorten, signaling women’s increased mobility: their movement outside the home, on bicycles, and as photographers. As sleeves expand, both physically and socially, the wearer expands her breadth.